Column

ColumnAll the world fits under the roof

Architecture first came to be not to be beautiful but to protect a human from the elements. The visual aesthetic was just a by-product of a space created for a purpose, determined by the materials used and the expertise of its builders, shaped by the rituals and culture of the dwellers. The way it feels, sounds, and smells is a non-visual architecture, the way it fills the space with use, narrative and the spatial rhythm is also a non-visual architecture.

It is initially a shelter from rain, heat, snow, wind, animals, and enemies. It is wood, grass, clay, straws, and stone – materials made to work together. It is a structure, simple, and reliable.

Architecture helped people connect with the land, establish a comfortable place to stay, and improve it further. Long sedentary lifestyles created distinctive architectural expressions that were unique to the communities of the region. Japanese and Lithuanian people, separated by thousands of kilometers of land and sea, shaped by different historical influences, created their homes in such a way that it bears an uncanny resemblance. However, the visual similarity is just a superficial level of the deeper story behind the traditional architecture of these nations.

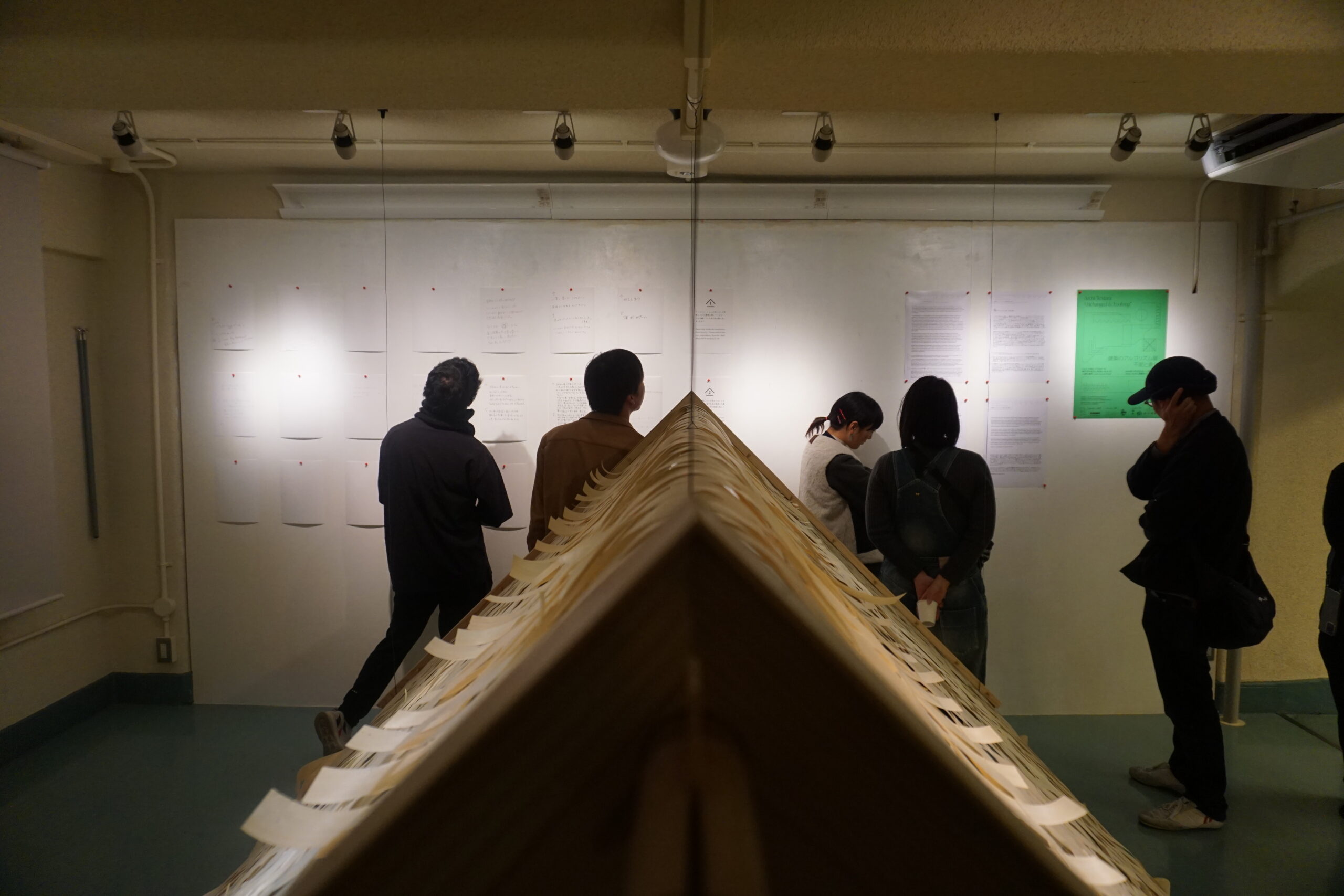

In this exhibition, we presented a crucial architectural element – a roof and offered visitors an essential architectural space to experience. Although this sensory installation offers just enough to be considered a piece of architecture and not a sculpture, it is a rich non-visual experience filled with smells of wood and tatami grass, light filtered through translucent wood, and the texture of natural materials. Unlike the architectural showcase, this exhibition essentially rethinks the creative logic conventionally applied in the field of architecture, not only presenting the methods of uncovering the space discovered with the blind people but also revealing the semantics of the non-visual environment.

We invited visitors to reconnect with the archetypal architectural space and reconsider their relationship with the spaces they encounter every day. What is there other than what’s visible? If you close your eyes, how do you remember it?

From our point of view, a deep, culturally charged, and socially productive understanding of the environment cannot be manifested only through a formal visual reading of architecture but requires a broader perspective, which is revealed by learning from certain social groups that perceive the world differently. But, if you think about it, don’t we all experience the surrounding space in our own special way? Each of us has a personal, intimate space somewhere, where we feel at peace, where we feel safe, feel comfortable…

During the two years of architectural research together, I, with my creative partner Tomomi Homma – the two architects and artists, representing the rich and interesting cultures of Lithuania and Japan – explored the phenomena of traditional architecture in both countries, trying to build an intercultural dialogue between the two countries and between us as artists. A dialogue, which would overcome both the language and visual barriers and would allow us through various senses – touch, smell, and hearing – to recognize universal architectural grammar responding to both cultures.

But what exactly is this grammar? How do we read the language of architecture, how do we understand the signs hidden between the facades and the structures? How to understand each other through the language of non-visual?

Tomomi spoke about how the thatched roofs from the Jomon period were meant to protect against rain, wind, and outside threats. Architecture according to her began with spaces enveloped in the kindness of safeguarding loved ones, gradually incorporating functionality. Technological advancements pushed functionality forward—straw floors were replaced with igusa, roofs embraced durable materials, and the pursuit of visual aesthetics progressed. Over time, functionality streamlined life, eliminating tatami and transitions, and seeking uniform spaces requiring minimal maintenance.

Tomomi also observed that catching the scent of fresh tatami after so long time, lying on thick, soft straw mats, one wonders why the inclination for a nap arises. Scents trigger memories. Each tatami square is the size of one thumb—within each square, sunlight shifts with the seasons. Each material brings forth endless discussions. What will children nurtured amidst room fragrances remember in the future?

ArchiTexturaLAB’s focus on non-visual architecture weaves tales, aiming to transcend eras and borders, making storytellers of people worldwide. With the collaboration of everyone in Kobe and Kyoto, we crafted gentle spaces using modern technology. Step inside, relax, and close your eyes. Please share the stories that come to mind here.