Column

ColumnYour Words

It was in the evening encroaching on the next day’s opening of Druskininkai Poetic Fall 2015, the international poetry festival in Lithuania, that I learned that Svetlana Alexievich, the Russian-language author from Belarus, had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Still a destination for tourists from the countries of Eastern Europe as the Baltic’s largest spa town, Druskininkai was that evening the site of a gathering of poets of diverse nationalities and even more diverse backgrounds. Among them were two poets from Belarus, Uladzimer Arlou and Valiantsina Aksak. Dressed in dark, subdued colors, this quiet pair seemed older than the other participants and kept always together like an elderly couple. The two took their breakfasts quietly at a small table apart from the round tables where other overseas guests from Estonia, Croatia and the like exchanged information in rapid and fluent English. When our eyes met, Valiantsina always had for me the barest of smiles. Without ever speaking a word.

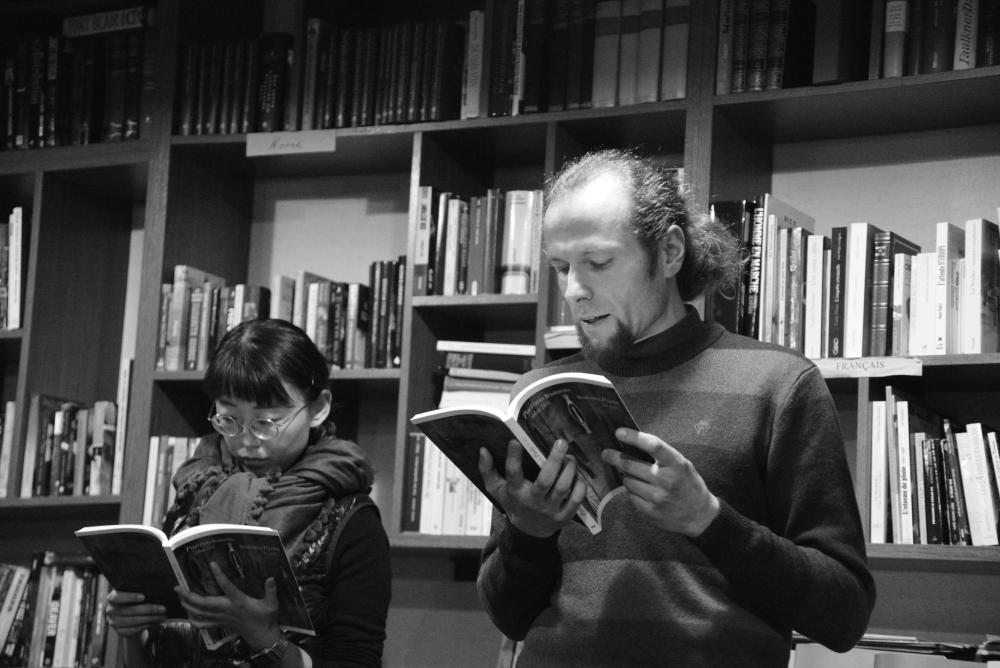

The morning after the news about Alexievich, the select trio of myself, Valiantsina and a Lithuanian poet named Ruta paid a visit to a local high school. After some delicious cake and tea in the headmaster’s office, we filed into the auditorium together with the students in the glistening morning sunlight, where we were introduced by the festival director, and we each read, with interpretation, one of our works in our own languages.

On introduction, Valiantsina stood squarely behind a chair and gave a bit of a long speech. Whether in Belarussian or in Russian I couldn’t tell. Unlike the weak smile she showed at breakfast, her face as she spoke glowed vibrantly. Like an educator, she delivered each word with impact. I seemed to hear the word “Alexievich”. Once, twice, then three times. And so I realized that she was relating that wonderful news to the students as a proud event for her own country.

The afternoon following that morning was spent in a discussion that was part of the main program of the festival. The theme this year was writer’s block. After the keynote by a team of Lithuanian poets joined by psychologists on the fear and the difficulties of being unable to write, the rest of us spoke out as we found fit about the obstacles we face in writing. While a very personal question, it is also one of prickly negotiation between the writer and the society that sustains him.

After I spoke about the twilight atmosphere shrouding the country of Japan since the earthquake, Uladzimer took the microphone. From his mouth issued a matter-of-fact recitation of the impunity of internet censorship in Belarus, how the country lacks an ambience permitting unguarded debate, how twenty years and more after independence from the Soviet Union the situation remains the same. (And just two days after this discussion, Belarus returned its government to power with 85% support in a plainly unfair election.)

I recalled Valiantsina’s face, full of hope, of just a few hours before. I remembered how she read her poem as though singing. I tried to imagine the mass of courage given these two poets by the selection for the Nobel of a journalist of sustained, if small, voice. The world would not change with the award. Even so, it did positively encourage in a small way the hearts of the people sitting next to me desiring free speech. Your words I pray for, and their safe conduct.

There’s one more thing I would like to put down here. It’s about Ruta, one of the poets who was on the school visit with me. Unfortunately, I don’t recall her surname. Nor was even one of her poems included in the anthology published to mark this year’s festival. But whenever I recall this festival, I will be sure to remember her. Curly blond hair in a short bob, red lipstick, big-boned, and with a fine physique. She didn’t make much of an impression on me at the school. But afterwards, in the touristy marketplace during a break in the festival program, while I was browsing a spice stall wondering what to buy for friends back home, she appeared beside me saying, “This one is the traditional spice of Lithuania,” and in halting English also supplied me with the recipe for a potato dish using the spice. Then at a stall selling organic herbal tea again she told me about a traditional Lithuanian drink made by a three-week infusion of vodka with herbal tea. But as I continued strolling alongside her, she said, “You needn’t stay with me,” and coolly set out in a different direction. When I later caught sight of her from afar, she was sitting alone on a bench in the sunlight, her eyes lowered to her notebook.

Then in the latter half of that discussion, only one response came to the moderator’s call for comments from the audience. It was Ruta.

She spoke in an emotional Lithuanian. Sometimes coiling her right hand into a fist and with tears welling in her eyes, she spoke in her native tongue. She spoke of how she had, due to circumstances at one point in her life, to live ten years in the far-off foreign land of Scotland, of her desperate isolation during that time, of the first five years writing and writing letters to her friends and of the last five years when she gave up even that. And now she was back in Lithuania: how big a decision it must have been for her to take part in this festival in order to speak out in her own language once more.

After the discussion I couldn’t help but race to her side. “I was impressed,” I told her. I felt like I too would cry if I said any more than that. Her looking at me speechlessly and with tears still in her eyes, we momentarily clasped each other in a tight hug.

Though I should have been worn out by the fast-paced festival program, by conversations about the state of poetry with poets I’d never met before, and by the intense cold that assaulted one just one step out of the hotel, I was excited, in the way of sparks quietly scattering, and didn’t expect to get to sleep anytime soon. So I struggled along to a bar called the Širdelé—, or “Heart”, for a beer to close out the day where the poets would gather night after night, and at a large table all the way in the back reserved for guests sat Uladzimer and Valiantsina. Just this side of them was festival committee chairman Kornelijus Platelis. And here was a Belarussian balsam liquor in a lovely bottle, procured by who knows whom from who knows where, going about among all the poets present. We raised our cups to Alexievich. The strong liquor, rich in color, tasted of curious plants, a collection of word leaves concentrated and distilled.